We are not only a product of our environment; we are co-creators of it.

— Stephen R. Covey

Chapter 3: The Interplay of Psychology and Sociology in the Parasitic Condition

The parasitic condition, as examined through the lenses of psychology and sociology, is not merely the result of individual traits or societal structures acting in isolation. Instead, it emerges from a dynamic interplay between the psychological tendencies of individuals and the broader social systems in which they operate. This chapter explores how these two dimensions interact, reinforcing and perpetuating the parasitic condition within society.

The Psychological Roots of Social Structures

At the foundation of any social structure is human behavior, driven by psychological needs and desires. The parasitic mindset—characterized by survival at the expense of others, manipulation, and a lack of empathy—can lead to the formation of social systems that reflect these traits on a larger scale. Individuals with parasitic tendencies may rise to positions of power, where they can shape institutions and cultural norms to benefit themselves and their class.

This process is not merely a matter of personal ambition. The psychological traits associated with parasitism—such as adaptability, resourcefulness, and the ability to manipulate others—are often rewarded in competitive social environments. In many societies, the ability to accumulate wealth, influence, and power is seen as a marker of success, regardless of the means by which it is achieved. As a result, those with parasitic tendencies may find themselves well-suited to thrive in systems that value these traits, leading to the emergence of a parasite class that wields significant influence over social and economic structures.

The Sociological Reinforcement of Parasitic Psychology

Once established, the social structures created by the parasite class can reinforce and perpetuate the psychological traits that underpin parasitism. The success and power enjoyed by the parasite class validate their behaviors, encouraging further exploitation and manipulation. This validation is often internalized by members of the parasite class, who come to see their position not as the result of exploitation but as a natural consequence of their abilities and efforts.

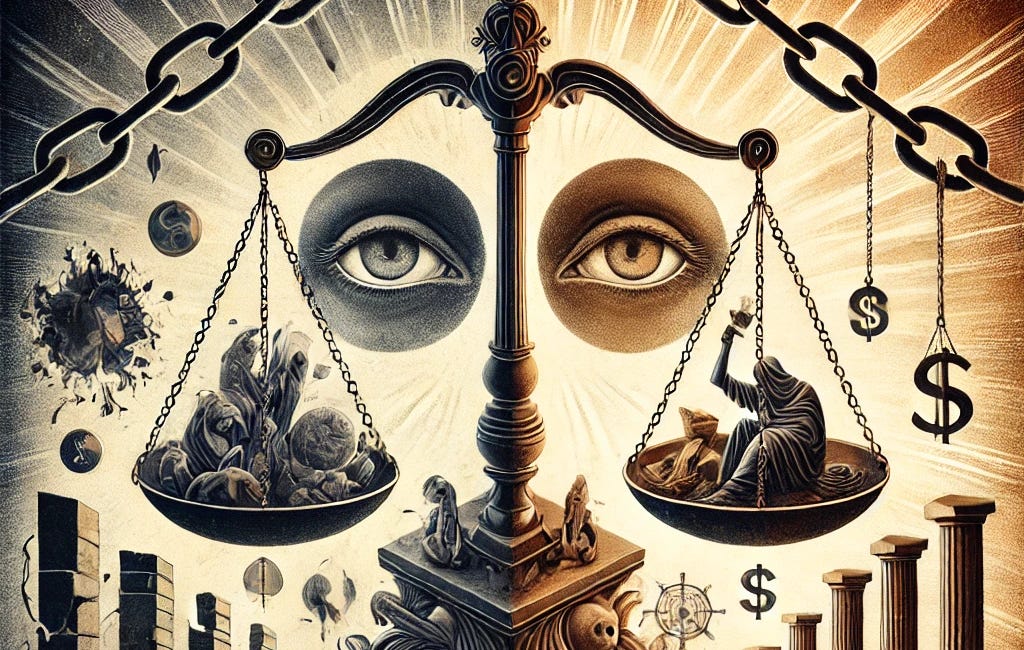

Moreover, the social systems dominated by the parasite class are designed to maintain their position of power. Through control of economic resources, political institutions, and cultural narratives, the parasite class creates an environment where parasitic behaviors are normalized and even celebrated. This normalization extends beyond the parasite class itself, influencing the broader population's perceptions of success, morality, and justice.

For example, in a society where wealth is equated with virtue, the actions of the parasite class are often seen as legitimate or even admirable. This cultural narrative can lead to a widespread acceptance of exploitation as a necessary or inevitable part of life, discouraging resistance and fostering complicity among the exploited. In this way, the social structures created by the parasite class serve to reinforce the psychological traits that sustain their power, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of exploitation.

Feedback Loops and the Entrenchment of Parasitism

The interplay between psychology and sociology in the parasitic condition creates powerful feedback loops that entrench parasitism within society. These loops operate on multiple levels, reinforcing the behaviors, beliefs, and structures that sustain the parasite class.

Psychological Validation and Social Reward: As individuals with parasitic tendencies succeed within the social structures dominated by the parasite class, their behaviors are validated and rewarded. This validation reinforces their sense of entitlement and superiority, leading to further exploitation. At the same time, the success of these individuals serves as a model for others, encouraging the adoption of similar behaviors.

Cultural Narratives and Social Control: The cultural narratives promoted by the parasite class shape public perception, making exploitation appear normal, natural, or even desirable. These narratives are disseminated through media, education, and other cultural institutions, creating a societal consensus that supports the status quo. This consensus, in turn, reinforces the power of the parasite class and discourages challenges to their authority.

Institutionalization of Parasitism: Over time, the behaviors and beliefs associated with parasitism become institutionalized, embedded in the laws, policies, and practices that govern society. This institutionalization makes it increasingly difficult to challenge the parasite class, as the very structures of society are designed to protect and perpetuate their power.

Alienation and Compliance: The exploitation perpetrated by the parasite class leads to alienation among the broader population, as individuals feel disconnected from the fruits of their labor and the decisions that affect their lives. This alienation can result in apathy and compliance, as people become resigned to their exploitation and unable to envision alternatives. In this way, the social structures created by the parasite class serve to suppress resistance and maintain their dominance.

Breaking the Cycle: Psychological and Sociological Interventions

While the parasitic condition is deeply entrenched, it is not immutable. Addressing the interplay between psychology and sociology in the parasitic condition requires both individual and collective efforts to disrupt the feedback loops that sustain it.

Cultivating Empathy and Awareness: On a psychological level, challenging the parasitic condition involves cultivating empathy, self-awareness, and a recognition of the interconnectedness of all people. By fostering a mindset that values cooperation and mutual support over exploitation, individuals can begin to move away from parasitic behaviors and contribute to the creation of more equitable social structures.

Promoting Critical Consciousness: Sociologically, it is essential to promote critical consciousness—the ability to recognize and challenge the social, political, and economic forces that perpetuate exploitation. Education, media, and cultural movements can play a crucial role in raising awareness of the parasitic condition and empowering people to resist it.

Reforming Social Structures: On a systemic level, addressing the parasitic condition requires reforms that reduce the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of the parasite class. This might involve redistributing resources, enacting policies that promote social and economic justice, and creating institutions that prioritize the common good over individual gain.

Building Alternative Models: Finally, breaking the cycle of parasitism involves building alternative models of social and economic organization that prioritize cooperation, sustainability, and equity. By creating spaces where parasitic behaviors are not rewarded, and where people are valued for their contributions to the collective well-being, it is possible to disrupt the feedback loops that sustain the parasitic condition and create a more just and humane society.

Conclusion

The interplay between psychology and sociology in the parasitic condition reveals a complex and self-perpetuating system of exploitation that shapes individual behavior and societal structures alike. By understanding how these dimensions interact, we can begin to challenge the parasitic condition at its roots, both within ourselves and within the systems that govern our lives. This requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the psychological, cultural, and institutional factors that sustain parasitism, and that promotes the development of a more empathetic, just, and equitable society.